Fixing our Shoji 👹🍣🎎 Wonderful Japan

Nothing is built to last forever - this seems to be the motto of most houses in Japan. In my home country, on the other hand, people often consider themselves lucky and happy if they can call an old building their own, which can often be a hundred years old. An English acquaintance recently said that his parents' house had probably been around for several centuries and that some of the buildings at his university had probably even seen the Middle Ages. Nobody thinks in such dimensions here in Japan, and as soon as your own house has survived a few decades, you start thinking about replacing it with a new one. Of course, this only happens if you can afford it, but in principle nobody likes to buy a house that is more than thirty years old. And if they do, it's better to tear it down and build a new one.

There are probably several reasons for this behavior, but it is clear that houses in Japan are built for wear and tear and not to last forever. Frequent earthquakes and high humidity, for example, are two factors that ensure that most buildings are not given a long life, but have to make way for something new one day in the foreseeable future.

It is also noticeable that many old buildings in Europe look much more stable and homely than buildings in Japan, which are only approaching half a century of age. It seems people don't renovated and modernized so much, so that decay sometimes seems to set in quite early.

Nevertheless, sometimes something needs to be repaired and improved, as not everyone can afford to build something new straight away. And some things need to be regularly refreshed to ensure that your home remains comfortable and pleasant.

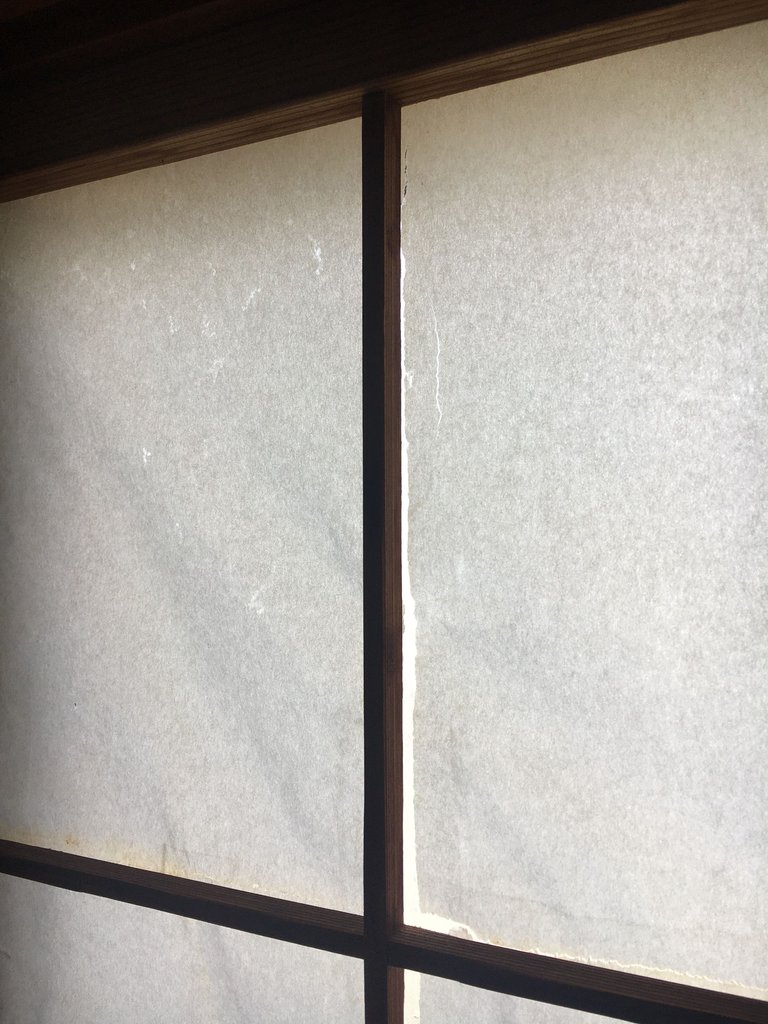

These include, above all, the shoji, the inner sliding windows or sliding doors covered with a thin piece of paper, which can still be found in many Japanese houses today. In very modern buildings, it might only be the tatami room that still has some shoji, but in our house there are quite some sliding windows that have suffered quite a bit over the years.

In the case of shoji, paper is not really patient and tends to tear quickly if touched unintentionally. Little by little, we are now setting about re-spanning them and making them a little prettier.

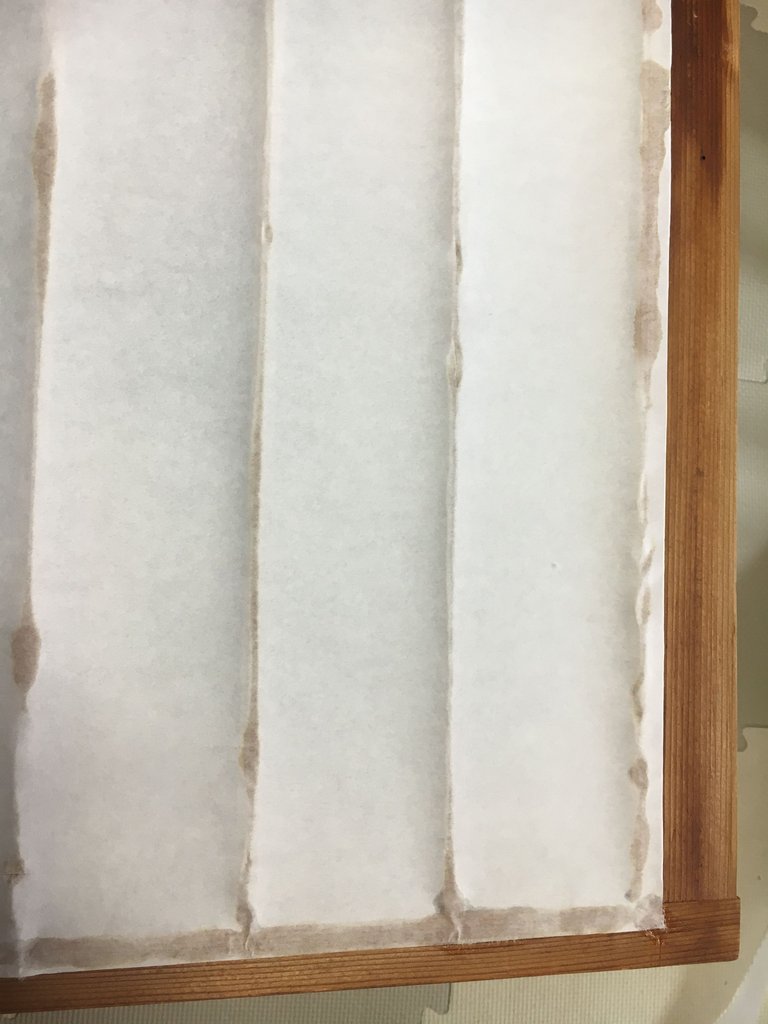

This is a photo of a comparatively harmless damage to one of our shoji. Unfortunately, there are other places that I would rather not tell you about.

If you don't renew all the shoji at once, the amount of work is actually manageable, but you should still allow yourself a little time for it. Especially if, like us, you don't have too much experience in this area. But sometimes you have no choice and have to do it yourself.

The first step is to remove the remains of the old paper covering, which can usually taken off quite easily and without leaving any residue after a few years of use. A little water helps where the old paper is a little more stubborn, and then you have the blank sliding window frame in front of you.

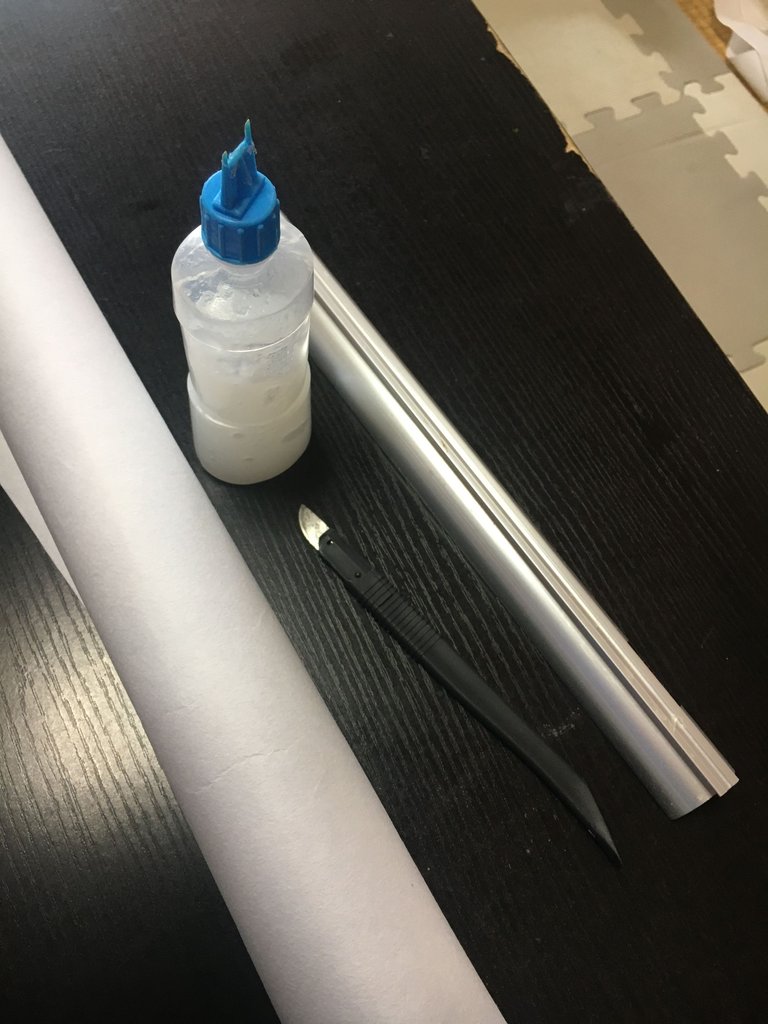

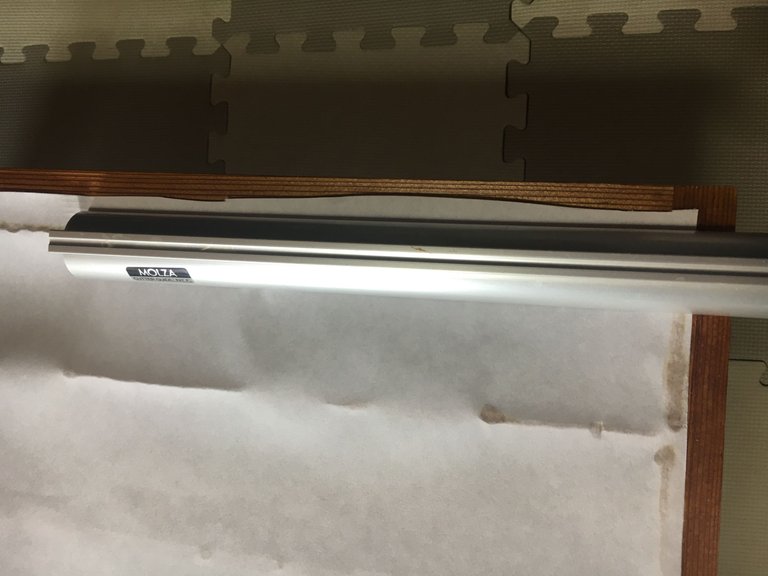

What you need now is new shoji paper, glue, a rail and a sharp knife to cut everything to size at the end. Sounds easy enough at first, but the devil is in the details.

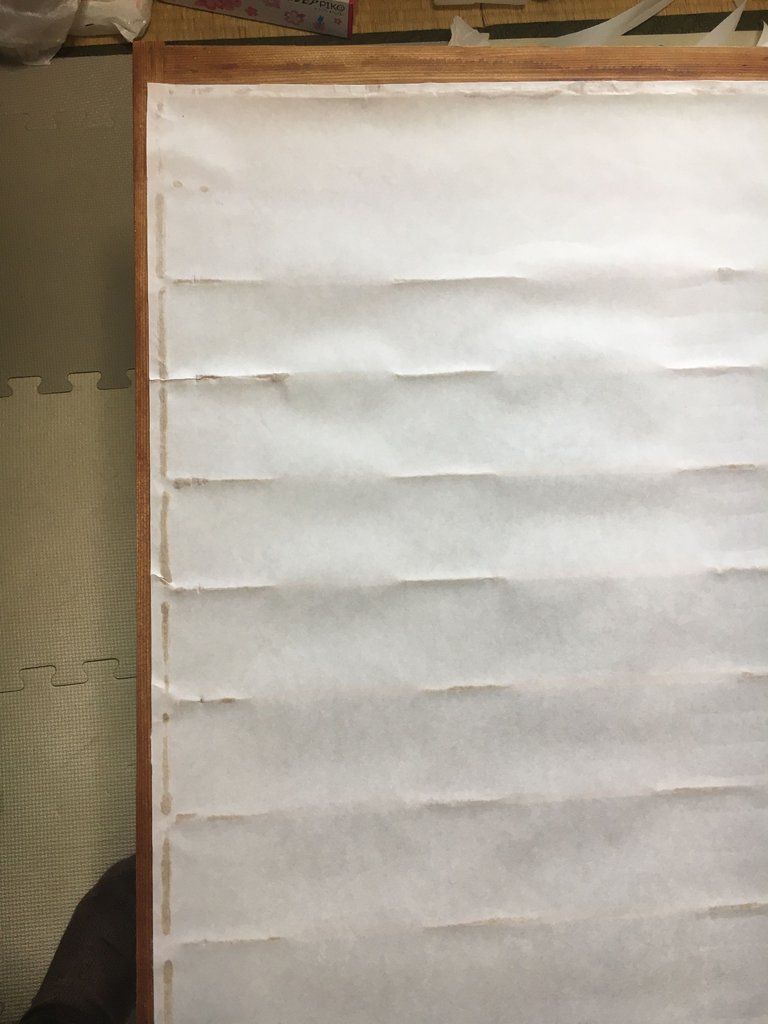

The frame is now coated with some adhesive just there, where the new paper is to be glued on. Our glue bottle has a rubber guide so that you can apply it exactly where you want it on the outside and on the cross struts. If you move a little too quickly, you will of course forget some places, but DIY enthusiasts will be familiar with this problem from wallpapering in their own home.

Next, apply the shoji paper and roll it tightly. Once from top to bottom or from left to right, and then cut it roughly for the first time.

Getting it thight is kinda tricky, because at first glance everything looks far too loose. But it should pull itself into shape a little at the end.

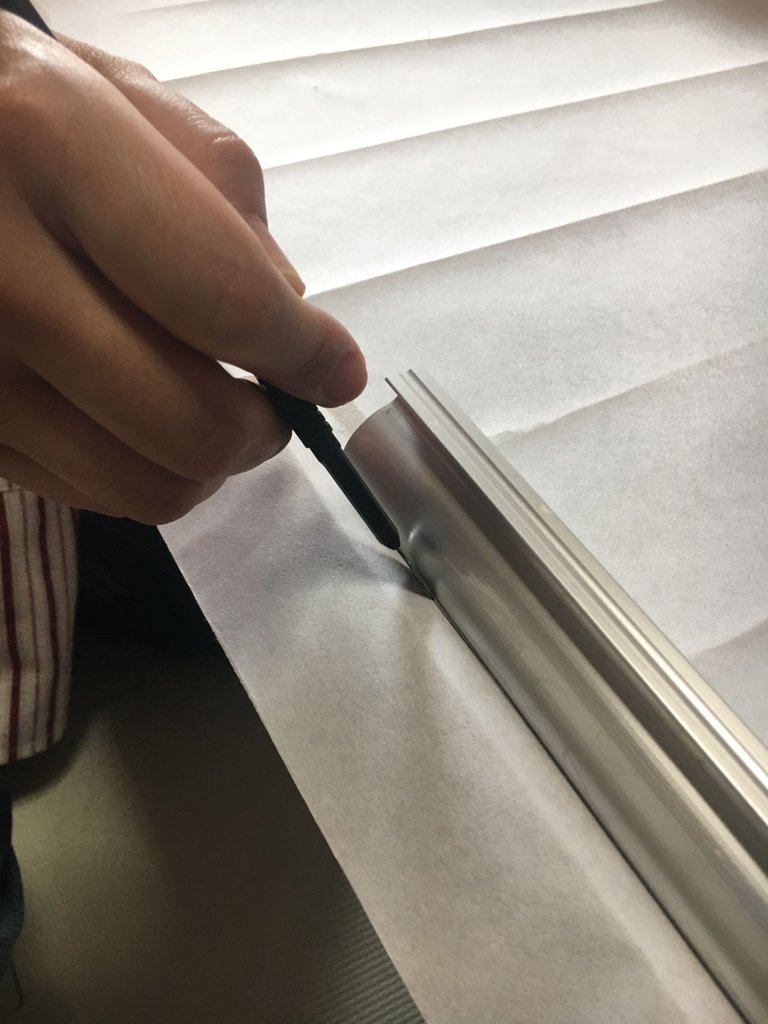

Now it's time for the fine cut, and you now need the knife, whereby a sharp cutter should be all you need here. Place the rail on the frame exactly where you want to make the cut and start cutting carefully.

Cutting and not tearing should be the motto, because the thin paper tears far too quickly, especially if it is still damp where you have left a little too much glue. So it's better to cut slowly and carefully so that you don't have double the work later.

But with a little patience, you quickly get the hang of it. Our knife was also sharp enough and we were able to cut our shoji paper quite quickly. And if something didn't look quite so nice at the edges, that wasn't a problem in the end. Fortunately, the side with the glue is not the side that you can see, but the one that remains hidden from view.

And in the end, the paper had also stretched and taken on the shape that was expected of it. Now it looks wonderfully white on our window frame and covers the real glas window behind it. As in many Japanese townhouses, the windows on the first floor are made of milk glass and nobody can look through, so the sole purpose of this shoji was to decorate and embellish our room. And for that it looked great again and will hopefully stay that way for a long time.

But as I said before, shoji are not made to last forever. Unfortunately, we have already discovered that in our house as well and so we are now in the process of repairing our shoji damage bit by bit. In the end, it's even a little fun, and when you're finished, you're of course delighted with the result of your work. And you learn and get a little better with every shoji, and finally you can brag about your work here in this blog.

What could be better?