Temný 21. srpen v Brně; Dark August 21st in Brno

Invaze vojsk Varšavské smlouvy do Československa v noci z 20. na 21. srpna 1968 znamenala pro mnoho lidí konec iluzí, ztrátu pocitu bezpečí a často i zaměstnání či domova. Vpád pěti armád si vyžádal lidské životy – historici zaznamenali 137 obětí přímo způsobených okupanty v prvních dnech invaze. Stovky rodin se musely vyrovnat se ztrátou manželů, otců, dětí i vnoučat.

EN: The invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact armies in the night of August 20–21, 1968, meant for many people the loss of illusions, the loss of a sense of security, and often also the loss of jobs or homes. The entry of five armies did not come without casualties – historians have recorded 137 deaths directly caused by the occupying forces in the first days of the invasion. Hundreds of families were left to cope with the loss of their loved ones – husbands, fathers, children and grandchildren.

V Brně byli v těchto dnech zastřeleni dva mladí lidé. Při prvním výročí okupace pak padly rukou českých komunistických milicionářů další dvě nevinné oběti. Tragédie dodnes připomínají pomníčky a pamětní desky v místech jejich smrti.

První a nejmladší obětí byl šestnáctiletý Josef Žemlička z Omic. S kamarádem se na malých motocyklech přijeli podívat, co se v Brně děje. Na Jihlavské ulici v Bohunicích, kde dopravu kontrolovala sovětská hlídka, zastavili u krajnice a sledovali dění. Když se jiný motorkář pokusil vojákům ujet, ruský voják vypálil dávku ze samopalu. Kulky zasáhly nevinného Josefa, který stál opodál.

Na východním okraji města, v Líšni, přišel o život Viliam Debnár. Vyzvedl z rekreačního zařízení svého pětiletého syna a vracel se s ním domů. Sovětská hlídka ho zastavila, vojákovi se však zdálo, že auto popojelo příliš daleko. Vystřelil dávku – pět kulek zasáhlo Viliama, jeho syn přežil jen zázrakem.

EN:

In the city of Brno, two young people were shot dead by soldiers of the Red Army. On the first anniversary of the occupation, another two innocent lives were lost – this time killed not by Soviet soldiers, but by members of the People’s Militias (a paramilitary force loyal to the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia). Today, these tragedies are commemorated by small memorials and plaques at the sites where the victims died.

The first and youngest victim was sixteen-year-old Josef Žemlička from the village of Omice. Out of curiosity, he and a friend rode their small motorcycles (locally nicknamed pionýry, popular mopeds at the time) to Brno to see what was happening. On Jihlavská Street in the Bohunice district, where Soviet soldiers were controlling traffic, they stopped at the roadside like many others and watched. When another motorcyclist tried to speed away from the soldiers, one of them fired a burst from his submachine gun. The bullets hit Josef, who was standing nearby.

On the eastern edge of the city, in Líšeň, another young man, Viliam Debnár, was shot dead. He had just picked up his five-year-old son from a recreational facility and was driving him home to Brno. When he pulled over as ordered by a Soviet patrol, one soldier thought he had stopped too far ahead and fired at the car. Viliam was hit by five bullets. His little son miraculously survived unharmed.

O rok později, 21. srpna 1969, zasáhla Brno vlna represí. Demonstraci proti okupaci rozehnali příslušníci VB spolu s ozbrojenými Lidovými milicemi. Mezi civilisty byla i osmnáctiletá Danuše Muzikářová se sestrou – šly jen na domluvenou schůzku s kamarádkou. Do bezpečí se však vrátila jen mladší sestra. Danuši našli zastřelenou v Úrazové nemocnici, přikrytou prostěradlem. Jen o pár metrů dál ležel další zastřelený – osmadvacetiletý Stanislav Valehrach z Kovalovic, kterého zasáhl milicionář na Orlí ulici.

Žádná z těchto vražd nebyla nikdy řádně vyšetřena. Z vyšších míst přicházely pokyny pachatele krýt a na rodiny byl vyvíjen nátlak, aby pohřby proběhly v tichosti. Přesto se jich účastnily tisíce lidí.

EN: A year later, on August 21, 1969, Brno saw another wave of violence. Demonstrations against the Soviet occupation were suppressed by the Public Security (the national police) with the help of armed members of the People’s Militias, often called the “armed fist of the working class.” Among the bystanders was eighteen-year-old Danuše Muzikářová, who had come to the city with her sister to meet a friend. They were not planning to demonstrate. Their father, whom they met on the way, warned them not to stay in town because it was unsafe, but the girls reassured him they would return quickly. Only the younger sister made it home. Danuše was later found dead in the University Trauma Hospital, her body covered by a sheet. Nearby lay another victim – twenty-eight-year-old Stanislav Valehrach from the village of Kovalovice – who had been shot by a militiaman in Orlí Street.

None of these murders was ever properly investigated. From higher authorities came instructions to protect the perpetrators, and pressure was put on the families of the victims to hold quiet funerals. Even so, thousands of people attended.

Symbolickým místem paměti je i pomník před branou Zetoru. Osudy Josefa Žemličky a Viliama Debnára totiž spojuje podnik ZKL Brno – Debnár zde pracoval jako elektrikář a mladý Žemlička se zde učil.

EN: A symbolic site of remembrance is also the memorial in front of the Zetor tractor factory. By a tragic coincidence, the two victims shot by Soviet soldiers on opposite sides of the city were connected by the ZKL Brno engineering works: Viliam Debnár worked there as an electrician, and Josef Žemlička was an apprentice at the same factory.

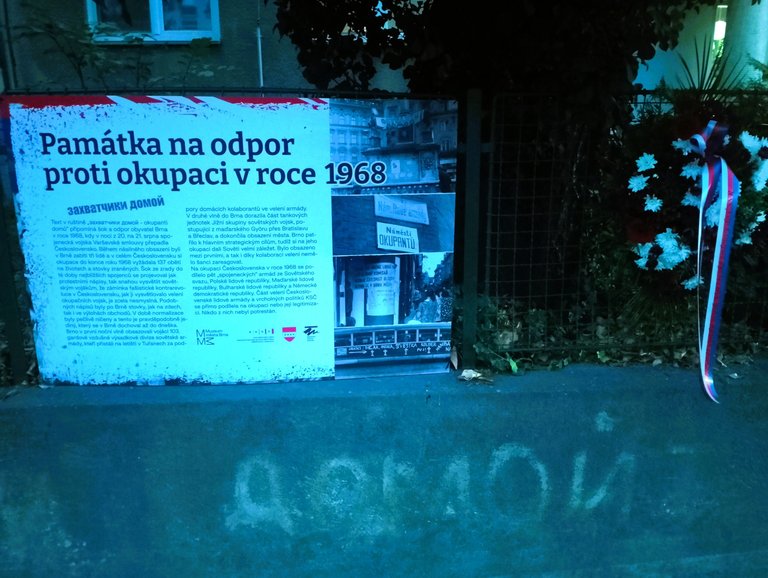

V době invaze se Češi snažili okupantům alespoň ztížit orientaci: měnili či přetáčeli směrovky, přepisovali názvy ulic, v azbuce psali výzvy k odchodu. Přestože většina těchto nápisů byla rychle odstraněna, jeden se dochoval dodnes – na Merhautově ulici lze stále vyčíst nápis: „Zachvatčiki domoj!“ – Okupanti, domů.

Čtyři mladé, zbytečně zmařené životy jsou mementem zrůdnosti režimu, v němž vraždy zůstaly nepotrestány a spravedlnost umlčena.

EN: During the invasion, Czechoslovak citizens tried to hinder the occupiers’ orientation by changing or repainting street signs and writing messages in Russian, urging the soldiers to go home. Most of these inscriptions were quickly removed by the regime’s forces, but one survived until today – on Merhautova Street, the faded writing can still be seen: “Zachvatčiki domoj” – “Occupiers, go home.”

The four needless deaths of these young people remain a lasting reminder of the cruelty of a regime in which murders went uninvestigated and justice was silenced.

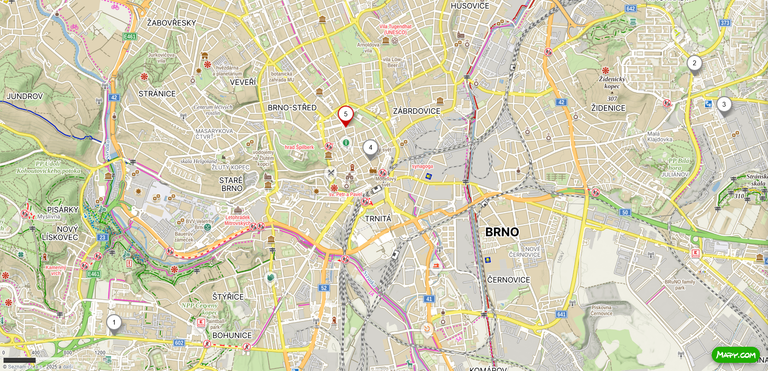

You can check out this post and your own profile on the map. Be part of the Worldmappin Community and join our Discord Channel to get in touch with other travelers, ask questions or just be updated on our latest features.

Congratulations, your post has been added to the TravelFeed Map! 🎉🥳🌴

Did you know you have your own profile map?

And every post has their own map too!

Want to have your post on the map too?

- Go to TravelFeed Map

- Click the create pin button

- Drag the marker to where your post should be. Zoom in if needed or use the search bar (top right).

- Copy and paste the generated code in your post (any Hive frontend)

- Or login with Hive Keychain or Hivesigner and click "create post" to post to Hive directly from TravelFeed

- Congrats, your post is now on the map!

PS: You can import your previous Pinmapple posts to the TravelFeed map.Opt Out

Congratulations @hairyfairy! Your post made the TravelFeed team happy so we have sent you our big smile. Keep up the good job. 😃

Thanks for using TravelFeed!

@for91days (TravelFeed team)

PS: Why not share your blog posts to your family and friends with the convenient sharing buttons on TravelFeed?

Thank you so much for your support.

After that August 1968, the light was turned off in Czechoslovakia for 20 years?

If I remember correctly, a little before 1990 the "teddy revolution" happened, when Czechoslovakia got rid of communism?

Yes, you are right. It is sad, that people forget very soon. In two months there are elections and we can expect communists back in government.

I hope the people will have their wits about them.

We didn't, so over the last 13 years more than half a million people left the country.

If that happens to you, the saying will start to apply: "Whoever leaves last, let him turn off the light".