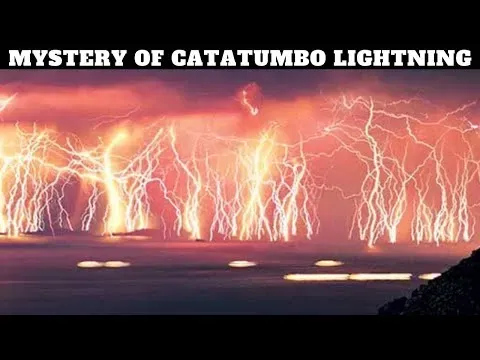

(ENG/ESP) the lightning of the catatumbo. el relámpago del catatumbo.

The Catatumbo lightning, better known historically as San Antonio lanterns or Maracaibo lanterns,1 is a meteorological phenomenon that develops in the basin of Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela,2 mainly in the southern area of said lake, to the lower basin of the Catatumbo River and beyond, in Colombia, where its name comes from (Catatumbo region).3 Scientists from the Scientific Modeling Center indicate that the most appropriate thing would be to talk about the lightning of the Catatumbo, because they tend to occur in multiple places every night, but from afar they are seen as if it were a single phenomenon.

This phenomenon is characterized by the appearance of a series of lightning bolts, electric discharges 'cloud earth', 'cloud earth' and 'between clouds' almost continuously, whose thunder can be heard almost uninterruptedly if you are under the storm. The discharges are the product of clouds of great vertical development or cumulonimbus that reach altitudes between 12 and 15 kilometers high, which is the maximum level of the troposphere in the tropics. Lightning can be observed at great distances at night. As the winds associated with the Low Level Night Current of the Lake Maracaibo Basin4 penetrate the surface of the lake in the afternoon (when evaporation is greatest) and are forced to rise by the contrast of cold air masses from the Perijá mountain system (3,750 m a.s.l.) and the Mérida Mountain Range, the Venezuelan branch of the Andes (up to approximately 5000 ms. n. m., approximately).

The origin of this phenomenon is in the orographic effect mentioned above due to these mountain ranges, whose air masses penetrate below the northeasterly winds, which are more humid and warm; Thus, clouds of great vertical development are produced, concentrated mainly in the Catatumbo River basin. This phenomenon is very easy to see from dozens of kilometers away, such as from Cúcuta, in Colombia, or from the plains highway between the cities of Guanare and Barinas to the south of the Mérida Mountain Range (as long as there are no clouds present at night).[citation needed] It occurs between April and November, producing electrical activity 95% of the night and/or up to 260 times a year and lasts up to 10 hours at night; Furthermore, this phenomenon can reach more than 90 discharges per minute.

However, Venezuelan environmentalist Erik Quiroga believes that storms could help repair damage to the ozone layer and is leading a campaign for the entire ecosystem that produces them to be recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

"Based on the fact that there is a cloud-to-cloud cycle of nighttime thunderstorms, it is possible that some of the ozone generated reaches the bottom of the ozone layer."

The Catatumbo lightning usually develops between the coordinates of 9°31'02.7"N and 9°39'47.4"N latitude and 72°06'57.2"W and 71°38'25.6"W longitude, which represents a very extensive area although, logically, not all of this area always has the same storm activity. The most remote areas of this extensive area are occupied by Motilon indigenous groups, who always tenaciously resisted domination by the Spanish first and those who tried to exploit their territory later. And it was very recently when they accepted the participation of Spanish Capuchin missionaries (already in the second half of the 20th century), who founded several mission towns such as El Tukuko and others. A simple meteorological station was installed in El Tukuko and in several years of observation the annual rainfall never fell below 4,000 mm, which serves to give an example of the rainfall in the area. In turn, this also explains the great flow of the Catatumbo River, which, with some 500 km in length, is navigable for much of its length. The final part of its course has numerous meanders and delivers an enormous amount of sediment to Lake Maracaibo, leading to a delta that has been built in the lake itself. In fact, if it were not for the fact that the lake constitutes an area of land subsidence (that is, a sedimentary or subsidence basin), the sediments contributed by said river would have completely covered the lake a long time ago.

El rayo del Catatumbo, más conocido históricamente como faroles de San Antonio o faroles de Maracaibo,1 es un fenómeno meteorológico que se desarrolla en la cuenca del lago de Maracaibo en Venezuela,2 principalmente en la zona sur de dicho lago, hasta la cuenca baja del río Catatumbo y más allá, en Colombia, de donde proviene su nombre (región del Catatumbo).3 Científicos del Centro de Modelamiento Científico indican que lo más apropiado sería hablar de los rayos del Catatumbo, porque suelen ocurrir en múltiples lugares cada noche, pero desde lejos se ven como si se tratara de un solo fenómeno.

Este fenómeno se caracteriza por la aparición de una serie de relámpagos, descargas eléctricas 'nube tierra', 'nube tierra' y 'entre nubes' de forma casi continua, cuyos truenos se pueden escuchar casi ininterrumpidamente si se está bajo la tormenta. Las descargas son producto de nubes de gran desarrollo vertical o cumulonimbus que alcanzan altitudes entre 12 y 15 kilómetros de altura, que es el nivel máximo de la troposfera en el trópico. Por la noche se pueden observar relámpagos a grandes distancias. Los vientos asociados a la Corriente Nocturna de Bajo Nivel de la Cuenca del Lago de Maracaibo4 penetran la superficie del lago en horas de la tarde (cuando la evaporación es mayor) y se ven obligados a ascender por el contraste de masas de aire frío provenientes del sistema montañoso de Perijá (3.750 m s.n.m.) y la Cordillera de Mérida, brazo venezolano de los Andes (hasta aproximadamente 5000 m. n. m., aproximadamente)

.

El origen de este fenómeno está en el efecto orográfico antes mencionado debido a estas sierras, cuyas masas de aire penetran por debajo de los vientos del noreste, que son más húmedos y cálidos; Se producen así nubes de gran desarrollo vertical, concentradas principalmente en la cuenca del río Catatumbo. Este fenómeno es muy fácil de ver desde decenas de kilómetros de distancia, como desde Cúcuta, en Colombia, o desde la carretera llanera entre las ciudades de Guanare y Barinas al sur de la Cordillera de Mérida (siempre que no haya nubes presentes en la noche). Ocurre entre abril y noviembre, produciendo actividad eléctrica el 95% de la noche y/o hasta 260 veces al año y dura hasta 10 horas por la noche; Además, este fenómeno puede alcanzar más de 90 descargas por minuto.

Sin embargo, el ambientalista venezolano Erik Quiroga cree que las tormentas podrían ayudar a reparar los daños a la capa de ozono y liderar una campaña para que todo el ecosistema que las produce sea reconocido como Patrimonio de la Humanidad por la Unesco.

"Basándonos en el hecho de que hay un ciclo de tormentas eléctricas nocturnas de nube a nube, es posible que parte del ozono generado llegue al fondo de la capa de ozono".

El rayo del Catatumbo suele desarrollarse entre las coordenadas 9°31'02.7"N y 9°39'47.4"N de latitud y 72°06'57.2"W y 71°38'25.6"W de longitud, lo que representa un área muy extensa aunque, lógicamente, no toda esta zona siempre tiene la misma actividad tormentosa. Las zonas más remotas de esta extensa zona están ocupadas por grupos indígenas motilones, quienes siempre resistieron tenazmente la dominación de los españoles primero y de quienes intentaron explotar su territorio después. Y fue muy recientemente cuando aceptaron la participación de misioneros capuchinos españoles (ya en la segunda mitad del siglo XX), quienes fundaron varios pueblos de misión como El Tukuko y otros. En El Tukuko se instaló una sencilla estación meteorológica y en varios años de observación las precipitaciones anuales nunca bajaron de los 4.000 mm, lo que sirve para dar un ejemplo de las precipitaciones en la zona. A su vez, esto también explica el gran caudal del río Catatumbo, que, con unos 500 km de longitud, es navegable en gran parte de su longitud. La parte final de su recorrido tiene numerosos meandros y entrega una enorme cantidad de sedimentos al lago de Maracaibo, dando lugar a un delta que se ha construido en el propio lago. De hecho, si no fuera porque el lago constituye una zona de hundimiento del terreno (es decir, una cuenca sedimentaria o de subsidencia), los sedimentos aportados por dicho río habrían cubierto por completo el lago hace mucho tiempo.